I recently returned from a 10-day trip to Rwanda and Uganda to track mountain gorillas in their natural habitat. Solo travelers can’t do this trip on their own, they must sign up for a government park ranger-led program and pay for a very expensive permit. The tours in both countries are done in groups of eight people. I normally do trips like this solo, but since I needed to do the gorilla trekking in a group, I decided to book the entire trip through Intrepid Tours and allow them to arrange all the transportation, lodging, and permits. I had a great time.

The gorillas can be seen in Rwanda, Uganda, and the Congo. The Congo isn’t a viable option for most folks as it is mostly lawless with minimal tourism infrastructure. In Rwanda, the gorillas are easy to find and the permits cost $1500 a day. In Uganda, there are more gorillas, they but they take a little longer to find. Ugandan permits cost only $700 a day. I chose to do the trekking in Uganda.

I wouldn’t have expected it, but Rwanda was a far more developed country than Uganda. It has a much better tourism infrastructure in place. Intrepid chose to start the tour in Rwanda because of better international flight schedules and more modern amenities for the beginning and end of the tour.

As you can imagine, there aren’t many direct flights into Kigali, Rwanda from the United States. I had to book a circuitous trip with United and Brussels Air to get there. The 27-hour trip (door to door) took me from Austin to Chicago to Brussels to Kigali. I don’t think I’ve flown United on an International trip for a long time. I was able to use credit card travel points to upgrade to their Polaris Business Class. I was impressed with their product. Good food. Lay flat seats. Their Polaris Business Class lounges were the best domestic lounge experience I’ve ever had. I will definitely consider flying with them again. The flights to Kigali all arrived on time and had no problems or delays.

United Polaris Business Class

I arrived in Kigali after dark and an eight-hour time change. Even though I got about five hours sleep on the plane, I was still worn out. I opted to go to bed early and spend the next day chilling while adjusting to the jet lag before I visited all the city’s genocide monuments and museums.

I slept 11 hours, had a leisurely breakfast, and then took a long walk outside to get a lay of the land. I went to the grocery store, had a massage at the hotel ($37 for an hour), read quite a bit by the pool and had an uninspiring dinner at a local restaurant close to the hotel.

No one goes to Rwanda for the food. Nile River Perch at a local restaurant

I stayed in the hotel made famous by the movie “Hotel Rwanda.” It’s kind of cool staying at the hotel that sheltered over 1000 refugees during the 1994 genocide. The perpetrators of the genocide murdered nearly a million Rwandans in a three month period. There is a small memorial fountain in the hotel parking lot that commemorates the hotel employees and guests who were killed.

The “Hotel Rwanda.” It looks different from the hotel in the movie because the movie was actually filmed in South Africa.

A few general impressions of Rwanda:

-The Rwandans seemed very kind and exceedingly polite. They (along with the Ugandans) are extremely soft spoken, even when talking to other locals. Despite the fact that most folks here are at least partially fluent in English, I had real difficulty interacting with the locals because I can’t hear what they are saying after a lifetime of exposure to incessant gunfire and explosions.

– I was definitely out of place while walking through the city. I saw lots of tourists at the hotel, but didn’t see a single other white guy outside the hotel gates. The locals seemed curious about my presence, but not in a menacing way. I didn’t feel uncomfortable at all. I wish more of the other tourists would get outside and experience the local culture.

– The country is impeccably clean. It’s one of the cleanest places I’ve ever been. Not a speck of litter in/on the streets, sidewalks, or parks. Once a month, the entire nation does volunteer work cleaning up their country. The clean up date just happened to be during my stay. During these Saturday morning nationwide cleanup sessions, it is actually illegal to drive on the roads unless someone is going to or from their job. Everyone else is expected to spend a couple hours cleaning public spaces during one Saturday morning a month.

– Loads of “security.” When the taxi driver was taking me to the hotel, he had to stop at the property’s front gate. Security guards checked for bombs underneath the car with a rolling mirror. They also had the taxi driver open the trunk, glove compartment, and center console to inspect for weapons and explosives.

The hotel sends all guest luggage through an X-ray machine and all guests must walk through a metal detector to go inside. There were also walk-through metal detectors at all the other hotels, the local mall, banks, restaurants, and government buildings. All of these metal detectors were staffed by completely unarmed security guards. I only saw two armed guards during my stay. Both were holding pistol gripped Winchester pump shotguns. One was outside a bank and one outside a large electronics store.

– I didn’t see a single cop during my first day. There were security guards everywhere. As I’ve noted in previous writings, people in the developing world don’t trust cops and can’t depend on them for protection. The areas with money hire their own security guards instead. We are already starting to see some of that in the USA right now. We’ll see a lot more of it in the future.

Most of the local folks I spoke with told me that Kigali is the safest city in Africa and that I shouldn’t worry about going anywhere in the city, day or night. My taxi driver from the airport was born in Burundi after his Rwandan parents fled the genocide. He told me that he has worked in several East African countries over the years, but moved back to Rwanda to raise his kids there because it is so much “safer” than other locations.

I think a lot of this “security” is theater, but people seem to believe that an unarmed security guard who isn’t even carrying a radio will protect them. The “boom barrier” stopping cars for the bomb check was made of aluminum and wasn’t even buried into the ground. Unsurprisingly, I set off every metal detector I went through. The guards just waved me past.

To avoid hassles, I ended up carrying a ceramic fixed blade knife (no longer made, so I can’t link to it) and my POM pepper spray. I had a couple guards look at my POM. I explained it was an asthma inhaler and they quickly lost interest. I ended up clipping my POM container to the waistband of my underwear behind my belt buckle when going through all the detectors. The walk-through detector would beep. I would lift up my shirt and show my metal belt buckle. The guards would let me through.

Each Rwandan hotel room has a “cock.” It works like a plug in air freshener but emits mosquito repellent instead.

I spent the next two days in Kigali doing a city tour, eating at some local restaurants, and visiting a few of the major Rwandan genocide memorials and museums. The genocide museums hit pretty hard. The experience was far more intense than seeing the pile of skulls at the Killing Fields in Cambodia.

Tower of skulls from my 2013 trip to the Cambodian Killing Fields

Even though I was in college when the genocide happened, I didn’t know all that much about it. I had no idea the role the Belgians and French had in the atrocity. I also had no idea that the genocide actually started with what are thought of as several “practice runs” as early as 1959. Each of those “practice genocides” killed hundreds to thousands per event and were classified as “tribal violence” by the foreign media. The world mostly ignored them.

The two largest killing sprees before the 1994 genocide occurred in the early 1990s. In those events, Tutsis who were targeted for assassination fled to large sports stadiums and churches. The Hutu killers chose not to engage them in those locations and they survived

In April of 1994 when the largest Rwandan genocide started, many of the Tutsis fled to local churches and sports complexes seeking refuge like in previous massacres. This time the Hutus breached their defenses and killed them en masse.

Two of the memorials I visited were churches. In one, over 5000 people were killed in a single worship room. In the other, 45,000 people were killed in the church and the town around it.

The bodies were removed, but otherwise the churches were left as they were immediately after the massacre. There were blood stains on the floors, the walls, and the ceilings. Bloody and torn clothing from all of the victims was carefully folded and hung from all of the church pews. Thousands of skulls crushed by clubs, hacked open by machetes, and breached by gunshot wounds were on display.

The most disturbing thing I saw was a section of wall in a church Sunday School classroom still darkly stained with blood and brains. It was there that the Hutus killed infants and toddlers by swinging them by the legs, smashing their heads up against the brick wall. There was a section of wall in there that was about eight feet long and six feet high where hundreds of kids were murdered by repeatedly smashing their heads up against the mud brick wall until they died.

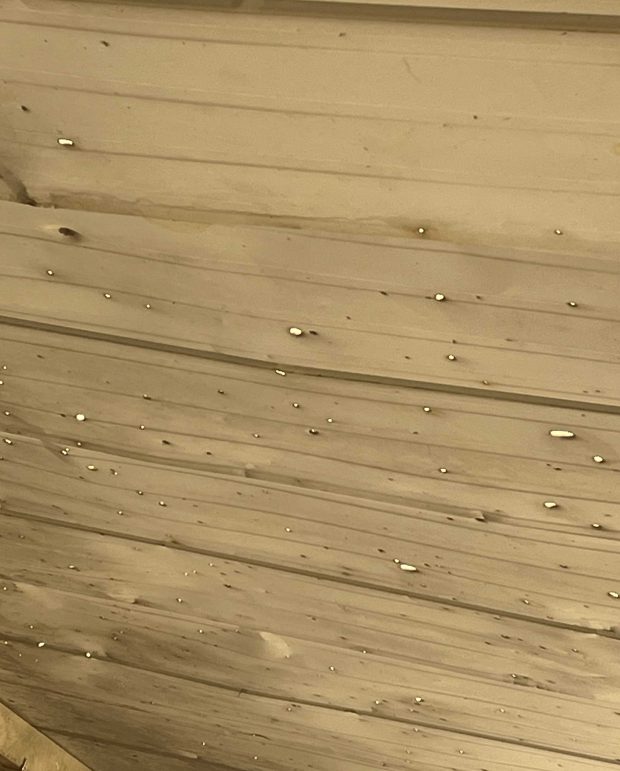

I didn’t take any photos of these areas. I honestly don’t want to remember them. I took the one photo below of the tin roof of the church where the largest number of victims were killed. The government soldiers threw grenades into the packed church, then let the juvenile militia members inside to kill whoever survived with clubs and machetes. The shrapnel holes from the grenades are still present in the church’s tin roof.

Tin church roof containing bullet and shrapnel holes from the massacre

I saw a lot of dead bodies and carnage in my police career, but these churches had a much bigger impact on me than any of the crime scenes I worked. Truly horrifying.

And for those of you who didn’t know, these were Rwandan citizens who were artificially categorized into two “tribes” by the Belgians for political control. This wasn’t tribal warfare. This was two groups of people pitted against each other for political gain. Best guesses are more than a million deaths (mostly women and children) in a little over three months. Countless more were raped, tortured, or seriously injured.

After spending two days learning about the history of this genocidal massacre, I can’t help but see similarities to the current situation in the USA.

In Rwanda, two groups of citizens who largely shared the majority of their values were polarized and pitted against each other for political gain. Does that sound familiar? If you ever get a chance to visit Rwanda, I would highly recommend studying the genocide. It might open your eyes a bit to the way we are being manipulated and what the potential future outcome might look like.

The tour guides and museums recommended the following books and movies as the best sources of information about the genocide.

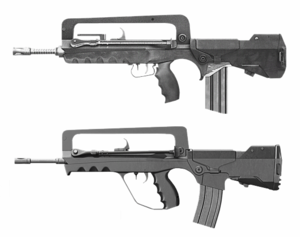

After the first day, I started seeing a few police officers. Most Rwandan traffic cops were unarmed. None of the cops or soldiers had handguns. In fact, I didn’t see a single handgun being carried anywhere in either Rwanda or Uganda. Each of the genocide memorials had a single cop (all females) assigned to guard the premises. These cops carried really beat up AK-47 rifles with no support gear or extra magazines. The cops I saw guarding government buildings and along the street at night were generally carrying French FAMAS bullpup rifles. That’s a strange weapon choice that I haven’t seen anywhere else in the world.

Would you know how to operate this rifle in an emergency?

Interestingly enough, the tour guides and taxi drivers stated that the cops in Rwanda couldn’t be bribed, unlike the cops in Uganda. In Rwanda, if an officer reports a bribery attempt, the person offering the bribe is arrested and can be sentenced to up to five years in prison. The police department then gives a financial incentive to the reporting officer that is equal to three times the bribery amount.

When I assess the relative safety of the foreign neighborhoods I visit, I primarily look for two things. In the daytime, I look for lots of working age men aimlessly hanging out in the street. That’s a bad sign. It signals unemployment. Unemployed young men are often bored and frustrated. They regularly turn to drugs and alcohol making their actions unpredictable. In Rwanda, I didn’t see anyone “hanging out.” Everyone was dressed professionally and moving purposely. That’s a big contrast to Uganda where there were lots of unemployed men standing along street corners.

The second thing I look for is whether or not people (especially women) are walking alone on the streets at night. Where I don’t see people on the street or I only see people walking in larger groups, I know an area may be dangerous. When I see local women walking home alone from work or exercising after dark, I know it’s generally a safe place. The streets of Rwanda were busy with lots of walkers and joggers after dark. The rural streets of Uganda were barren after sundown.

After a couple days in Kigali, we hopped into a Land Cruiser and took the five hour drive across the border into Uganda. Crossing the border by foot into Uganda was a typical exercise in third world bureaucracy. We first had to stand in front of a large mobile thermometer to ensure we didn’t have fevers. Then a nurse asked to see our Yellow Fever vaccination record. I had mine, but a couple in my group didn’t. The nurse asked if they had taken the vaccination. Both group members had, they just didn’t bring their vaccine cards. The nurse let them in. She had the vaccines available at the border crossing in the event someone wasn’t vaccinated.

After the health check we shuttled between four different service windows checking passports and visas before we were granted entry. The tour guide with our vehicle entered by merely showing his passport to the soldier manning the border gate. There was no vehicle search going into Uganda.

The drive was a bit chaotic and rough, but quite scenic. Rural Africa looks very different from the streets of America.

Rwandan roadside market

Ugandan children carrying water from a public well to their homes without indoor plumbing.

Ugandans working to turn the clay soil into bricks for home construction

Lake near the Uganda/Rwanda border

After another 90 minutes driving on fairly rough dirt roads and we arrived at the Nkuringo Bwindi Gorilla Lodge. We stayed three nights in the lodge. It was quite nice with four-course meals included as part of the stay. There was a bar with inexpensive beer and free WiFi in the public areas. The lodge contained six different individual cabins high on a hillside overlooking the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, one of only three places on the planet where mountain gorillas are thriving.

My cabin in the gorilla lodge

Sunset looking into the Congo from the gorilla lodge

We had an after-dinner lecture from a local park ranger about the mountain gorillas and what to expect on our trek the following day. We all went to bed early for a 0530 wake up call for our jungle trek.

We woke early, had breakfast, and then headed to the park (about 45 minutes drive away). When we arrived, park officials took down information from our passports and we had an orientation to what to expect from the gorillas.

There were eight “habituated” gorilla families in the area of the park we visited. Each family could get a single one-hour visit from a group of eight humans each day. The naturalists knew roughly where each family group’s territory was, but once in the area we would have to track them. Tracking gorillas through dense jungle at 7000 feet of altitude and almost vertical ascents and descents kicked my ass. It was literal bushwhacking with a machete following gorilla poop.

I was lucky enough to find and see two different mountain gorilla family units. Most folks only find one.We found a family, but it wasn’t the one we were hunting. We had to quickly walk past them so that they could be visited by a different group of humans. It took about two and a half hours of rough hiking to find the family we were seeking. The first gorilla we saw was the silverback. He was seated facing away from our group and wasn’t the least bit bothered by our presence.

First Gorilla sighting

As we were watching the silverback, another gorilla casually strolled right through our group. We followed the gorillas and hung out with them as they ate and played for more than an hour. During most of that time I had four to six wild gorillas as close as about five feet away. The rest of the 14 member gorilla family stayed within about 25 meters of us. It was a rough trek, but well worth it. Amazingly cool to see silverbacks in the wild within touching distance.

I purposely only took a few photographs so that I could better enjoy merely being in the presence of these amazing creatures. Here are a couple of the pics I snapped.

After spending a little over an hour with the gorilla family, we hiked about an hour out to a place along the road where our driver could pick us up. All in all, our hike was a little over seven miles, but the brush was so dense that it took 4.5 total hours to complete.

The following day, some of the group paid an additional $700 to repeat the experience while some others went bird watching. I chose to hire a local guide to show me the town closest to the lodge where we were staying. We walked into town and spent about four hours checking out the local restaurants (2), school, bar, blacksmith shop, and herbalist. It was enlightening.

The town

Restaurant #1

Restaurant #2

As appealing as these food establishments looked, I didn’t eat in either. The stunning lack of local customers despite it being lunch time made me question if if was worth getting sick to taste the local fare. I decided it wasn’t.

I did go to the local bar. This was the nicest bar in town.

I had a shot of their local moonshine. It’s a gin made with sorghum and bananas. Rough.

Banana Gin. That tasted nothing like bananas.

The locally made sorghum beer wasn’t bad. Very malty and sweet.

The village blacksmith was turning rebar into a machete and the local herbalist showed me the plants he most commonly uses to treat his patients.

The closest school was actually a private school. All parents pay for their Ugandan children to attend school. The public schools cost about $3.00 a month. The private school near the lodge costs $40.00 a trimester (without boarding costs). It was so full it had to reject students. When I walked past the school, little kids were playing a volleyball game using a crushed plastic soda bottle for a ball. These were the kids with money and they couldn’t even afford the most basic ball for recess.

The next day we headed back to Kigali. Of course the truck broke down on the way. The rough roads broke one of the wheel studs attaching the wheel to the axle. We couldn’t stop because we were an hour away from the nearest garage, so we limped into town. It was an interesting experience watching the mechanics use a tiny car scissor jack and a bunch of bricks to jack up the Land Cruiser. The missing wheel stud caused the wheel to move on the other studs. The holes through the wheel became severely elongated. The guys at the gas station actually put a bunch of metal washers under the lug nuts and sent us on our way. TIA (this is Africa).

I had one more day in Kigali before my flight left late the next night. I found a nice restaurant and enjoyed a meal of steak filet medallions. On the taxi ride to the airport, I encountered another new experience. When entering airport grounds, the cab driver drove into what looked like an automated car wash. He put the cab in neutral and ordered me out. It was a whole car X-ray machine to check for explosives and drugs. All passengers had to exit and go through a metal detector before entering airport property. I’ve never seen that before in any of the 60-some countries I’ve visited. Here are the only two pictures I got of the car X-ray machine before the local cop yelled at me to stop taking photos.

My flights home using Air Rwanda and United were not quite as smooth. All three were delayed. My plane connection in Heathrow was a complete nightmare. I’m glad my flight was late because after three terminal changes and security checks, I almost missed it. For what it’s worth so far this year, 22 of my 42 flights have been delayed or cancelled. Last year at this time 29 of 37 total flights had been delayed or cancelled. Although flying is still a nightmare, it seems to be getting a little better than last year.

For what it’s worth, my friend Nick Hughes from Warriors Krav Maga didn’t believe my travel account as written above. He found a newspaper alleging that I was involved in smuggling a shaved gorilla back into the United States. Maybe he’s right. I’ll leave it for you to decide.