Written by Greg Ellifritz

Last week I was reading a forum post about the utility of the flanking maneuver in a battlefield context. Flanking is a critical battle strategy and even the greenest of soldiers understands its importance.

Yet the idea is generally not taught in a law enforcement context. Ask a cop about flanking and you will get nothing but a puzzled look unless the cop has prior military service. In some contexts (like team active shooter response), flanking is expressly forbidden. This is something that really needs to change.

I am firmly against militarizing our domestic law enforcement officers. That’s not what I’m talking about. Cops don’t need to adopt a military methodology for patrol. Police work and a military invasion have different goals. But gunfighting is gunfighting, whether it is in the context of a military battle or if it is a cop taking fire from armed robbers. We should be looking to other disciplines and seeing if we can adopt what works for them in order to improve our survival outcomes.

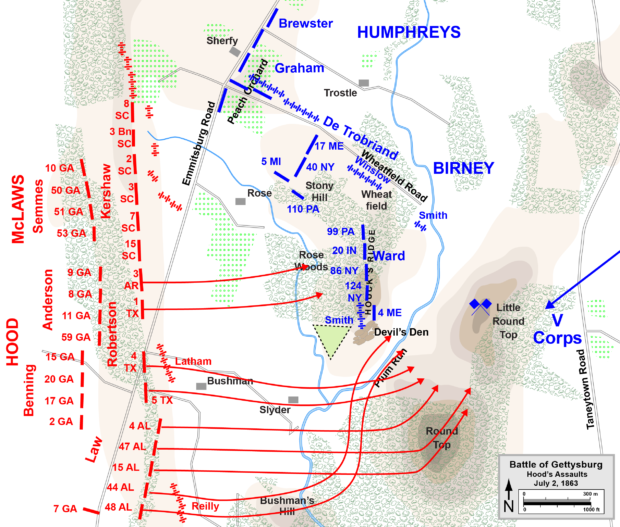

Take this issue of flanking. It’s the idea of fixing the enemy in position and then sending a second force around to the rear or side so that you can split the enemy’s attention and fire on them from more than one direction. It doesn’t have to be complex….think of every old Western movie you’ve seen where the sheriff says “You guys go in the front door to distract him and I’ll go around the back to take him by surprise.” That’s flanking.

I’ve been to several instructor-level training schools on police active shooter response. Most of these schools advocate the “posse” approach. Officers wait outside while the killer shoots until they can establish a team of three to six officers who then go in to find and engage the shooter. This tactic has its place, but I think it’s outdated as far as current active shooter protocols go. Nonetheless, it is still commonly taught.

One of the strict guidelines that has been presented at every class I’ve attended is that “the team never splits up.” The idea behind always sticking together is that it allows the officers to maintain 360 degree security coverage and to avoid crossfires. Rigid adherence to this idea can also get officers killed in some situations.

I remember the first time I recognized the weakness of not teaching how to flank. I was playing the role of the “bad guy” in a large multi-agency active shooter scenario training session. As I was shooting inside a four-story office building, a team of six officers was sent in to find and neutralize me.

I kept shooting until I saw the team (who was using a diamond formation). The team leader stopped, using the corner of a hallway for cover to engage me. I was out in the open and the team was behind cover. But, due to their positioning, only the team leader was able to fire on me. All the other officers waited impotently behind him, unable to shoot without hitting their leader. I ended up taking out four out of their six officers before I was hit.

The only thing I could remember thinking was “why didn’t they just split up the team and send half of them around to get me from the other side of the room?” I would have been completely unable to counter that type of a tactic. I might have shot one or two people (if I was lucky), but I certainly wouldn’t have been able to take out 75% of their team.

If you are a cop, I would urge you to break away from some of the entrenched dogma that forms our tactics. We need to look to other disciplines in order to grow and improve. Learn about flanking and figure out how you can use it to your advantage in combat.

Battle of Gettysburg showing flanking maneuver courtesy of Wikipedia