Written by- Greg Ellifritz

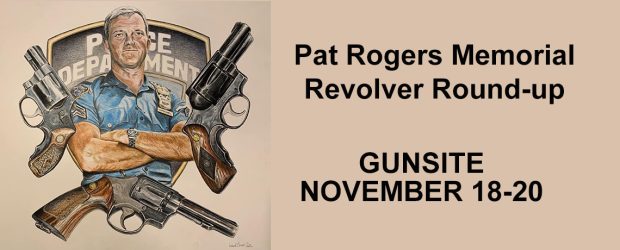

When I was teaching at the Gunsite Pat Rogers Memorial Revolver Roundup last month (sign up for next year), I had a couple students using revolvers chambered in 9mm caliber. One of the students asked me about best choices for a defensive loads for a 9mm revolver.

Looking at the Ballistics by the Inch Page, it’s pretty clear to see that out of similar barrel lengths, the 9mm tends to have 100-200 feet per second more velocity than the same weight bullet in .38 special. I don’t see how you could go wrong with carrying any of the good factory hollowpoint rounds in your 9mm revolver. All will probably perform better than a similar weight .38 special bullet.

With that said, there are a couple of issues that must be resolved before you ever even start thinking about terminal ballistics.

The first issue is called “bullet jump.” This is a phenomenon where bullets start pulling free of their cases because of recoil and the fact that the bullet crimp is different than most revolver cartridges. The best description of the problem I’ve seen was in an article titled “9mm Revolver Ammo: Avoiding Bullet Jump & Other Issues” by George Harris. In the article, Harris states:

“Another concern is the inertia placed on the bullet in the case during recoil. The amount of force generated at firing in the lighter revolvers tends to unseat the bullet, moving it forward and changing the internal ballistics of the cartridge from one shot to another. In more-extreme cases, the bullet(s) may be displaced forward far enough to protrude from the front of the cylinder, which essentially locks the cylinder in place and prevents a 9mm revolver from firing.”

This issue is usually confined to the lightest 9mm revolver types. In the full sized guns, or the newer full size guns and the heavier steel versions like the old S&W 947, bullet jump doesn’t happen as commonly. I see the issue present itself most commonly in the Ruger LCR 9mm revolvers.

The Smith 547 as mentioned above

Before anything else, your gun must shoot. If bullets are jumping the crimp and making your gun malfunction, stay away from that load for defensive use.

The second issue is that I’ve seen a wider variety of 9mm revolvers that don’t shoot certain bullet weights anywhere near the point of aim. It isn’t unusual to see 9mm revolver loads that hit six to twelve inches away from the point of aim when using certain bullet weights, even at close range.

If you found a load that doesn’t jump the crimp, your next concern is making sure that round hits to the point of aim. That’s very much an individual variation. Some 9mm revolvers shoot best with a certain load. Others digest almost anything. Pick a load that hits close to your sights.

It’s only once you’ve solved these two pressing issues that we can even start considering terminal ballistics. I would much prefer shooting a ball round that hits to the sights and doesn’t jump the crimp than carrying a premium hollowpoint that exhibits bullet jump or shoots eight inches high.

Now we must start considering the ballistic problems endemic in short barreled guns and consider the fact that the revolver’s cylinder gap affects both accuracy and velocity.

With a few exceptions, most defensive ammunition is designed to expand within a relatively small and specific velocity window. When bullets designed to expand out of full size duty pistols are fired in guns with shorter barrels, they won’t expand as violently due to the loss of velocity. For most well designed hollowpoint bullets, expansion is generally optimal when velocities exceed 1000 feet per second.

The heavier (147 grain) 9mm bullets and non +P loads aren’t likely to come anywhere close to this velocity threshold when fired out of a short barreled revolver. In fact, the 147 grain loads will probably be closer to 800 feet per second. That’s probably not enough for reliable expansion, especially through heavier clothing. Lighter weight bullets will expand more out of a shorter barrel.

Almost all revolver shooters understand that escaping gasses from the revolver cylinder gap also negatively effect velocity. What most people don’t know is that heavier bullets lose more velocity from the cylinder gap than lighter bullets. Again looking at the BBTI Page, we see that a 125 grain Corbon Hollow point out of a two inch barrel loses 40 feet per second of velocity between being shot from a gun with no cylinder gap and one that is .006 inches. A Speer 135 grain Gold Dot loses 55 feet per second. The 158 gain loads lose up to 60 feet per second.

A twenty feet per second velocity difference may not seem like a big deal, but if we are looking for optimal expansion, it may make a difference. The general trend between all .38 bullets is that the heavier the bullet, the more velocity is lost through the cylinder gap. There’s no reason not to assume that the same trend will hold true for 9mm revolver bullets as well.

After taking a look at the velocity and cylinder gap issues, I would have to recommend a light to medium weight bullet for the 9mm revolvers. I would personally look at the 124 grain Speer Gold Dot, the 124 gain Federal HST, and the 127 grain Winchester Ranger. The 115 grain loads wouldn’t be off limits either, depending on how well they shot to my revolver’s point of aim. The over expansion of those loads in the full sized pistols would be mitigated by the shorter revolver barrels.

If I was carrying a 9mm wheel gun, I would choose a 115-127 grain name brand quality hollow point round that didn’t jump the crimp and shot the closest to the point of aim with my revolver. Then I’d buy a whole bunch of those rounds and stop worrying about “stopping power.”