*This is a guest posting from a friend and student who wishes to remain anonymous (you’ll see why after you read the article). The author is a “gun guy” with military special operations experience and a lot of formal firearms training under his belt. He is attending a police academy with the hopes of becoming a part time local police officer or deputy sheriff to serve his community.

What follows is a “gun guy’s” take on police academy firearms training. Most of you all reading this have likely attended formal firearms training classes. You might like to see how police firearms training compares. Prepare to be underwhelmed.

I think you’ll enjoy the information.

– Greg

I am currently a cadet in a local police academy. Having just completed our firearms training module, I thought I would like share what law enforcement firearms training looks like from someone who has trained outside of LE circles. Cops are often perceived as experts on firearms, but my experience would indicate otherwise.

Two Huge Caveats

First, there were some truly phenomenal instructors, great cops, and wonderful people teaching in this course. This isn’t to denigrate or criticize any of them. I definitely point out some knowledge gaps, but everyone is ignorant of something and this doesn’t mean these instructors are bad people or bad instructors. To be clear, there was some bad instruction, and – as you will see – tons of room for improvement in entry-level law enforcement firearms training. Still, I sincerely appreciate the hard work of all the instructors. They aren’t providing bad training out of malice; it is most likely that they are giving students the best class they are capable of within budgetary limitations and their own knowledge.

Also, being friends with and having spoken to some of the instructors, some recognize the shortcomings of the training. They’d like to change it but are hamstrung by a variety of factors including budget, training time, the inflexibility of senior course cadre, etc. Again, I just want to make it clear that this isn’t to bash the course instructors, just to give readers an unfiltered look at how cops are trained.

Second, what is true of this academy is not true of all agencies/states/police academies. Some agencies have substantially better training than this. Some may have substantially worse training. This is a sample size of one academy that is probably somewhere near the low middle. This academy is a general academy, good for state certification, and thus employment, at any law enforcement agency in the state. Even within the state, there are some doing better and some doing worse, so take it for what it’s worth.

A Little Background on Me

I’m not your typical police academy cadet. I’m in my mid-40s and already have a full-time job that I don’t plan to leave. This is just something I’ve wanted to do as a way to be more involved in my community. I’m doing well in the academy; I am on track to be the honor graduate, am in the top 2 or 3 academically, I had the highest overall scores on the range, and despite being over twice as old as some students, am in the top 10% of the class physically. I point this out so you know I don’t have an axe to grind with the course or the faculty.

My firearms training background is pretty extensive. I am former special operator and gun-carrying government contractor. I have trained with many phenomenal instructors since leaving active duty including (in alphabetical order): Tim Chandler, Kyle Defoor, Greg Ellifritz, Erik Gelhaus, Tom Givens, Chuck Haggard, Simon Golob, Rob & Matt Haught, John Hearne, Ashton Ray, Brian Searcy, Mike Seeklander, Dustin Solomon, and Lee Weems. Additionally, I shoot probably a thousand rounds a month in structured practice sessions, on my own.

I have written for gun magazines printed on dead trees including GUNS and American Handgunner. I’ve also written for variety of firearms blogs including Lucky Gunner Lounge and Gun University. I’ve started and still own a successful firearms blog and a separate personal blog. I read tons of books on firearms employment, history, etc.

I do not claim to be an expert in firearms or training. I don’t currently carry a firearm professionally, and I don’t currently teach. I guess you could call me a very serious enthusiast. Hopefully this gives me enough credibility to honestly evaluate the state-mandated firearms training course I am about to describe.

Run of Show

This class was 48 hours in length. This is more than most Citizens get in a lifetime, so it sounds like a lot. Among those there were 8 classroom hours. The remaining 40 hours were spent on the range, the overarching goal of which was to get students through the state qualification course of fire. The actual shooting consisted mostly of shooting the qualification courses of fire over and over. I have never attended training that was so geared toward testing. After everyone had passed the qualification, handguns were immediately secured and there was some shotgun “familiarization fire.”

Classroom: We had two nights (8 hours) of classroom training. instructors had to cram a lot of material including describing the actions of single- and double-action revolvers, single-action, double-action, and striker-fired pistols. This is important stuff for cops to know as they will likely encounter all kinds of cheap guns. One instructor brought in personally owned firearms in all categories to demonstrate, but students got no hands-on time whatsoever.

On the second night of class, we covered the fundamentals of marksmanship: stance, drawing, grip, sight alignment, sight picture. There was some (but very minimal) practice with these techniques with our blue guns. The worst part of the classroom instruction was that it was almost two weeks prior to our first night on the range, so students remembered very little of what was taught in the classroom by the time they were actually shooting.

Night 1: I am attending a night class, so our shooting was actually done at night. The range was outdoors and was lighted reasonably well, but was still far from an ideal environment to teach brand-new shooters. That night we did some dry practice, which was a good thing. Then we shot steel reduced-size silhouettes. We never loaded more than two rounds at a time. Very basic, and very structured. I didn’t think this was the worst for a first night of training.

Nights 2 – 6: Qualifications, over and over and over. On the last two of those nights, we shot for score. In total, each student probably shot somewhere around 600 rounds.

Saturdays: There were two, eight-hour Saturdays. On the first Saturday we did a shotgun qual. This wasn’t mandatory, but a nice add-on (side note, the shotguns were Mossberg 500s with ghost rings and 870s with rifle sights – not bad shotguns at all, but definitely could have benefited from shorter SGA stocks) . This wasn’t awful, but there was a LOT of wasted time. The second Saturday was a dynamic course of fire with lots of steel, moving targets, decision drills, etc. This was certainly fun, but probably didn’t meet most students where they are. And again, there was a ton of wasted time; it was an eight-hour day for three runs through the course.

The Good…ish

Let’s take a look at the positives first. I did get a few things out of this week on the range.

9mm Appreciation

We qualified with Glock 22s (.40 S&W, Gen5) with iron sights. This week was truly 9mm appreciation for me, but it did teach me something. I don’t have much history with the .40 S&W cartridge. In the military I mostly carried and shot a 1911 in .45 ACP, and after my military career was issued and carried Glocks (17 and 19). Since then I’ve mostly carried 9mms personally.

The academy gave me a bit of experience with the .40 – enough to know that I can run a .40 if I have to…but I don’t really want to. It isn’t painful and it’s not that I “can’t handle it,” I just don’t get back on target as quickly. For the larger student body, shooting .40 probably wasn’t ideal. I think these guns were purchased just before all the agencies in my area began their recent transition to 9mm guns. On the bright side, students qualifying with the Glock 22 should have no problem qualifying at their agency with a Glock 17 or 45.

As a side-note, this was also pistol-mounted optic appreciation. I have finally fully moved to pistol-mounted optics. I’m still pretty decent with irons, but not like I was twenty (or even five) years ago. I’m fortunate that the agency where I will work has fully embraced pistol-mounted optics.

Low Light Qualification

This actually wasn’t the worst qualification I’ve ever shot. It is fired at 3, 7, 10, and 15 yards. The lighting conditions vary; at 3 yards there is no external light source. At seven yards you are required to use a handheld flashlight for some stages, and blue lights for others. At ten yards you have “low beams,” and at fifteen yards you have “high beams” (low beams and high beams were simulated by lights mounted at the range). This is probably the most exposure I’ve had to nighttime shooting in a formal course since I was in the military.

Instructor to Student Ratio

The number of instructors to students was outstanding! This was the one area in which this course far surpassed all paid, open-enrollment classes I have attended. We were never on the range with fewer than one instructor per three students, and it was usually one instructor for every two students. All (OK, most) of the instructors were professional, knowledgeable, helpful, and approachable.

The Bad

Now let’s get into the things that unequivocally could have been better.

Training to/for the Qual

The “training” was essentially just shooting the qual over and over. I assumed we’d go to the range, spend a couple days working fundamentals, maybe shoot a trial run of the qual, work some more fundamentals, and then qualify. That was not the case; this class was 100% qualification oriented.

I believe this created an unhealthy mindset in many of the students. All who passed (and everyone passed) the qualification think they are “good.” I heard a lot of comments like:

• “I just have to get through the qual, then I’m good to go!”

• “I just need a 70!”

• “I’ll be good enough by Friday to pass.”

Many of the students have little idea what “good” really looks like. Another large percentage of them are not gun people (which blows my mind!) and carrying a firearm is only incidental to why they want to be cops. Quite a few perceive the firearm as just something you have to carry around or as a symbol of their new career. Very few view the sidearm as the tool they may have to one day use, lying on their back on pavement, hands covered in their own blood, to take the life of someone who is trying his best to murder them with a shovel.

I see this as a dangerous attitude, yet one that is fully embraced by instructors. The purpose of qualifications is to validate your training. Ideally you should not be trained to the qualification, but rather trained, and the qualification should serve as evidence of proficiency gained through said training. Unfortunately, coupled with unrealistic scoring (my next subject). Passing this qualification course does not, in any way whatsoever, prepare students for the realities of fighting for their lives.

Suggestion: Focus on building actual skill. Spend most of your days training people to actually shoot, not just come dragging across the finish line with a 70 (yes, a 70% is passing). Use drills like ball-and-dummy to identify problems and help people work through them rather than continuing to repeat techniques that don’t work. THEN shoot the qualification, work on problem areas, and repeat.

Unrealistic Anatomy & Generous Scoring

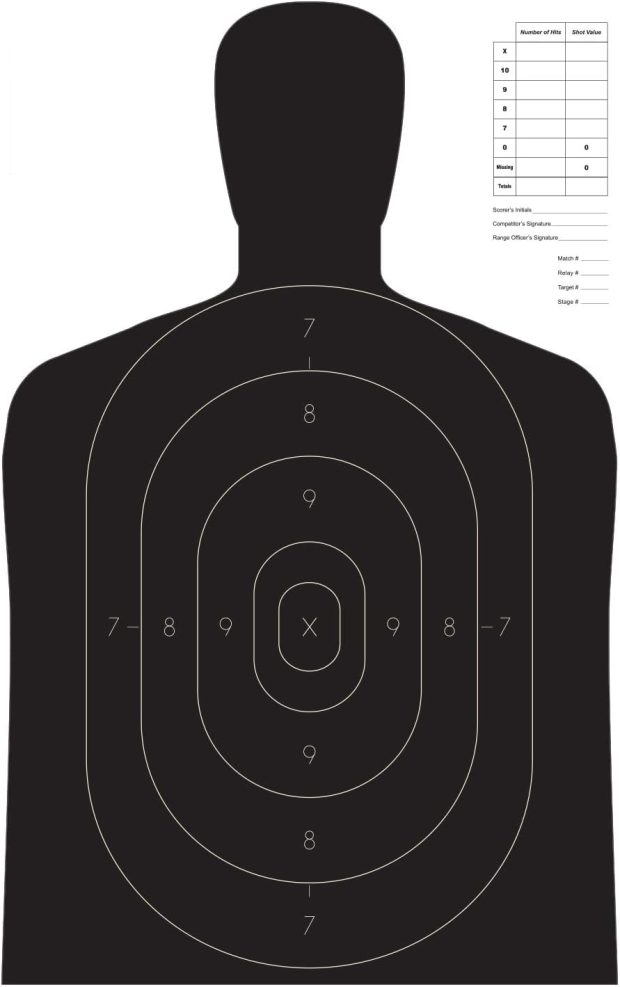

The qualification target is the much maligned (at least in the training community) B-27. This silhouette is physically larger than I am. Additionally, it trains you to shoot at the center X-ring, which is in the upper abdomen of a human being. Maybe the state has recognized the impotence of its firearms training program, and this gives students the greatest possibility of a hit anywhere on the human body?

Jokes aside, the scoring area is terribly unrealistic. Anything within the 8-ring is considered full value. Many knowledgeable shooters and instructors consider the “down zero” or “-0” zone on an IDPA silhouette to be a decent size target on a human being. It is an 8-inch circle, high center mass. The area of this circle is just over 50 square inches. The 8-ring of a B-27 silhouette is 11.8 x 17.7 inches, or about 200 square inches. That is a MASSIVE area that runs, on my body, nipple to nipple, from my sternal notch to just below my belly button (or as presented on the target, from my nipple line to my pubic bone). I can promise you, all of those hits in such a broad area are not equally valuable in stopping a determined threat.

There are two problems here. First, cops trained on the B-27 are taught to shoot at the solar plexus rather than high in the chest where the heart and great vessels lie. The other problem is that it trains them that a hit pretty much anywhere on the target is just as good as a hit anywhere else. This is not the case.

Suggestion: Instructors are bound by the state to use the B-27 qualification target. However, I’m a firm believer in “aim small, miss small.” All practice was done only on massive B-27s, where hits anywhere on the target count substantially toward your score. I would recommend training on a smaller target, progressing to one with a less clearly-defined scoring area (perhaps with some subdued anatomy so students could understand where they are hitting in relation to a live human), then moving to the larger target for qualification only…but part of me imagines there’s probably some state rule against that, too.

No Demonstrations

This one was so ubiquitous and universal that I didn’t even notice it until it was pointed out: there were no demonstrations of anything. Everything was described, but nothing (or very near nothing) was demonstrated by the instructors. Very few of the instructors fired even a single round on the range.

If I went to an open-enrollment course and the instructor was unwilling to demonstrate what he wanted me to do, I would have serious doubts about his abilities. Demonstrating for students accomplishes several things. It proves that you can do what you are teaching. It shows them how to do it. And if you are teaching you should be able to demonstrate it well, so it shows students the art of the possible.

Suggestion: Demonstrate for your students! Show them what you want them to do, and show them that it can be done near-perfectly. I question some of the firearms instructors’ shooting ability because I’ve never seen them shoot a single round.

Lack of Historical Knowledge

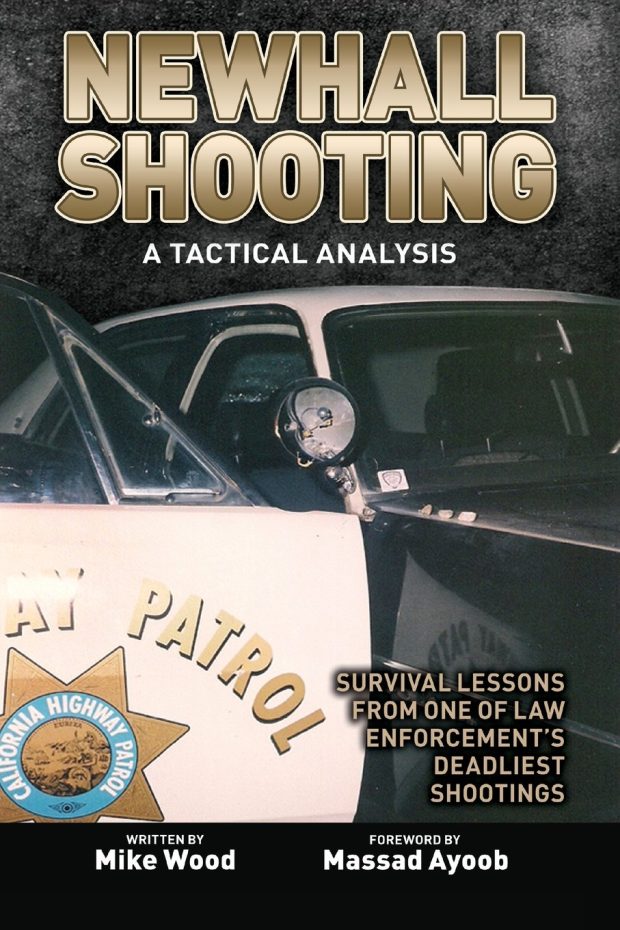

I was constantly amazed to hear some pretty famous events brought up and completely butchered. One was the Newhall shooting. Mike Wood, author of the definitive account of the 1970 Newhall shooting, is a close, personal friend of mine, and I know that the “brass in the pocket” myth has largely been debunked. But of course, I heard the same story I heard in boot camp 25 years ago: “Troopers somewhere out in California – I think it was LA – were found dead with brass in their pockets because that’s how they did it on the range.” I think the overall message of that is a good one, but it’s factually inaccurate.

There are several other examples that I won’t bore you with. I think the problem here is that law enforcement officers largely seek training only within law enforcement circles*. Like the Citizen population they serve, few cops read books. All of the cops who have mentioned additional training have mostly mentioned the same small, insular, local group of trainers. This seems to have created some self-reinforcing group-think.

Suggestion: read books, follow blogs written by SMEs, train with industry experts outside of your normal thought-circle.

*Keep in mind this is a generalization. At every open-enrollment course I have been to in the last five years, there has been at least one cop spending his own time and money to train. Those guys are out there, but they are the exception, not the rule.

The Ugly

No Safety Brief

When I attend an open-enrollment shooting class, a competition, or even a casual range session with some of the most serious shooters I know, I inevitably hear a safety brief. It usually covers the following:

• the four firearms safety rules,

• primary and alternate 911 callers (the people who best know how to describe the range’s location),

• primary and alternate medics (the people with the highest or most applicable medical credentials),

• the nearest medical facility and drivers (people familiar with the area).

Having designated callers avoids the “diffusion of responsibility problem (“I thought someone else was calling“). Having designated medics ensures the most qualified people are giving care and everyone else isn’t crowding around. This is really important shit if someone gets shot!

During our six nights and two Saturdays on the range, I did not hear a single safety brief beyond “don’t shoot to the left or right or over the berm.” This didn’t make me feel good, especially being out there with brand-new shooters, as well as plenty of “I been shooting all my life” types. As regimented as our firearms training is, I’m baffled that the state doesn’t mandate that a safety brief be given at the beginning of each range session.

Also, to my knowledge, there was no serious first aid kit on the range. If there was, I never saw it. I made sure to keep my personally owned, fully-stocked IFAK in my cargo pocket at all times.

Suggestion: give a comprehensive safety brief at the beginning of each and every range session. No ifs, ands, or buts, no matter if “everyone” has heard it a million times (because someone, guaranteed, has heard it zero times). Also, keep a first-aid kit on the range in a consistent, conspicuous location. Ensure it is stocked sufficiently to treat gunshot wounds.

Horrible Blue Gun Discipline

Another thing that concerned me throughout the class (and, keep in mind, this was not confined to the firearms module) was discipline with blue guns. We are issued inert, plastic Glocks to carry on our duty belts throughout the course. They are used occasionally during defensive tactics, traffic stops, and other practical modules, before we had firearms training. When they were first issued, I told the class to treat them like real guns (keep them in the holster, don’t point them at people, finger off the trigger, etc.).

This immediately went out the window when instructors were seen treating blue/red guns carelessly, doing what I would call “fucking around” with them. From that point on, blue gun discipline was out the window. Students would walk around, drawing down on each other, and no one said a word. I’d made my opinion known on it, but with instructors treating blue guns carelessly it was a losing battle. Additionally, our classroom hands-on with drawing, grip, stance, etc. was conducted at our desks. We were in three rows, so students in the second and third rows were pointing guns at other students’ backs, completely ignoring safe gun-handling habits* and reinforcing the idea that blue guns could be handled as something other than firearms.

I use the word “habit” very deliberately. Safety is not “range safety,” it is “100% of the time” safety and should be made a durable habit, not a mode we switch into on the range. Seeing a student whip out a blue gun and point it at another was so common I had legitimate concerns that this habit would carry over to the range with a loaded Glock 22.

Suggestion: build strong safety habits by extending loaded firearms rules to blue guns. Obviously, this rule is bent during training scenarios, but it shouldn’t be completely broken with students twirling guns on their fingers (true story) and drawing down on each other when bored.

*This doubly pissed me off because I got yelled at for “anticipating” a command to draw. “You anticipate a command on the range and I’m going to bust your ass! Now is the time to start acting like you are on the range!” I did not point out that we are not on the range, and I knew that because if we were, we wouldn’t be lined up firing-squad style, shooting into each other’s’ backs. Instead, I just said, “yes sir.” I said “yes sir” a lot during this class.

Blue Gun Missed Opportunity

The mishandling of blue guns also leads me to another point: the opportunity to use them as more than a mere “prop” during scenarios was completely lost. Fifteen of minutes of instruction on a proper draw, and five minutes a night dry practicing the draw, grip, and stance (in a safe direction, of course) would have made these students much more effective gun handlers. Instead, they were left to figure all that stuff out on their own.

Suggestion: get maximum training value out of blue guns but training students how to draw and grip the gun before they are figuring it out in the middle of scenario…and reinforcing bad habits.

Shotgun Stuff

I’m not a shotgun expert, but I am a serious and devoted student of the shotgun. I’ve taken a couple courses, have two more lined up this year, and have earned a Sym-Tac coin. I try hard to stay up on current shotgun trends and to maintain a high level of skill with the shotgun. Some of the stuff I heard in the shotgun portion was shocking.

One student was advised to take his finger off the trigger between shots because the shotgun might slam-fire. A slam-fire occurs with some older shotguns when the firing pin stays forward as long as the trigger is pulled. When the shell is chambered and the bolt goes forward, the shot is fired. This hasn’t been an issue in nearly 100 years of shotgun design, and applies to no shotguns of modern manufacture. Wtf?

Next up, students were told that birdshot is an effective CQB round. Good grief, where do I even begin with this one? Birdshot is for birds that weigh ounces, and for busting fragile sporting clays. Buckshot is for stopping human-sized individuals.

And speaking of buckshot, I was impressed to note that the buckshot used was Federal Low-Recoil, 9-pellet, Flite Control load (PD 13200). The eight-pellet version is the absolute pinnacle of social buckshot, but this is still an outstanding load. Unfortunately, the slugs were full-power Federal TruBall slugs moving out at 1,600 FPS (PB127 RS). They were positively abusive, even to me. Low-recoil slugs exist (the Federal PB127 LRS being a good example) but unlike Flite Control, seem relatively unknown.

Exacerbating the recoil of the slugs was that no instruction whatsoever was given in the Push-Pull technique of recoil mitigation. Instead, students were told to pull as hard as possible with both hands back into the shoulder. This does not make for a pleasant shotgun shooting experience! Unfortunately, some students were completely turned off to the shotgun and have no desire to ever pick one up again.

Suggestion: train outside of law enforcement circles. Darryl Bolke, Tim Chandler, Greg Ellifritz, Steve Fisher, Tom Givens, Rob & Matt Haught all offer outstanding, modern shotgun instruction!

Conclusion

My apologies that this was so long – I know it’s a lot of reading. Part of this was probably just an outlet for some of my frustration with the firearms portion of this class. More importantly, though, I hope this gives some insight in to how well (or not) most cops are trained to used their sidearms. I have nothing but respect for the law enforcement officers out there. I have even more now as I sit through this class, watching people come in five nights a week, tired from work, to sit through a class that will get them a dangerous job starting between $18 and $22 and hour.

As much as I (and doubtlessly you) respect them, keep in mind that as a group they are not gunfighters or firearms experts. The people you are depending on to help you may have passed with a 70%…which means they might have completely missed the entire target stand several times. You need to be prepared to take care of yourself. Chances are (at for readers of Greg’s blog) you are much better than the cops who are going to come “save” you.