*Fair warning, The following text contains a frank discussion of cancer, death, and sexual function. If any of those topics offends you, move on and avoid reading this piece. If those topics don’t bother you, read on to learn about the challenges I’ve been experiencing during the last few years.

– Greg

While a lot of you are enjoying the holidays with family and friends, I’m mentally preparing for an early January surgery that could have permanent, life-altering side effects. I have prostate cancer and my future is a bit uncertain at this time.

Some of you already know about my cancer. Most of you probably do not. I’m not trying to be secretive but I haven’t talked about it in a public forum or on my websites for the very simple reason that people treat you differently when they know you aren’t far from an encounter with the Grim Reaper. I don’t like that.

Soon after my diagnosis, I quickly learned that talking about my cancer makes a lot of folks very uncomfortable. I don’t like bringing pain into the lives of the people I care about. I also don’t like talking about the disease and my shortened shelf life in every future conversation. It’s mentally taxing. I’d rather remain positive, so I generally choose to avoid focusing on the problems I’m having. It makes life much more pleasant.

But now I’m at a turning point in the progression of my disease and feel like I owe you all a bit of an explanation. Here’s the full story.

But long term survival wasn’t my primary goal.

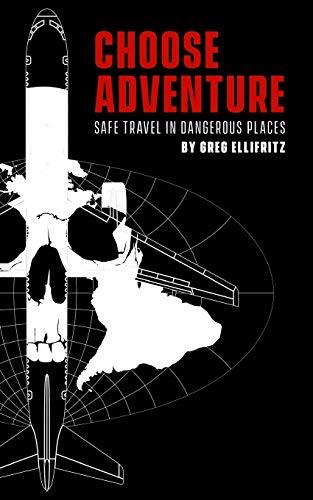

I’ve had a great life. I’ve accomplished everything I’ve ever wanted to accomplish. I’ve done more crazy things and had more adventures than any three “normal” people I know. I got a master’s degree while working full time. I reached the heights of success both in my police career and my training business. I published an Amazon #1 best selling book. I traveled all over the world and loved more than my fair share of beautiful women. I had no serious romantic interests to protect and no kids to depend on me. I’ve had a great run. Dying an early death wasn’t a big concern for me.

Being involved in a life-threatening occupation for 25 years forced me come to terms with my mortality at a very young age. I had also dealt with several previous cancer scares. In 2015, I was incorrectly diagnosed with adrenal cancer. In 2018, I battled melanoma. I had three other more minor skin cancers surgically removed. The thought of dying from cancer was not a new one and it didn’t worry me.

Furthermore, I had done a lot of spiritual work in the jungles of Peru and Costa Rica working with shamans using the traditional jungle drugs called ayahuasca and vilca (a tree bark snuff containing several versions of the potent drug DMT). Those psychedelic experiences allowed me to experience the idea of death and provided me with a couple of very memorable near-death experiences. As master shaman Don Howard Lawler told me “Dying is easy after you’ve done it a few times. It’s living that is hard.”

I learned that the vast majority of radical prostatectomy patients were impotent after the surgery. Even worse, the doctors found a creative way to hide this impotence in their research studies. They re-classified impotence in patients who have had a prostatectomy.

Before my cancer diagnosis, if I was to go to the doctor after being unable to achieve or maintain an erection, I would be diagnosed with “erectile dysfunction” and prescribed a pill or an injection to help me get an erection again.

After prostate surgery, they don’t classify men as having erectile dysfunction unless the pills/injections fail to work. I learned that only a very small percentage of prostatectomy patients were able to achieve a natural erection without drugs post surgery. Depending on the study cited, there was up to a 80% rate of erectile dysfunction rate even with Viagra and penile injections.

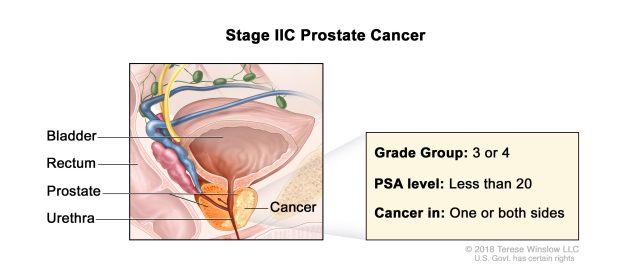

Even worse, one of my tumors is located very close to one of the two nerves that control sexual function. During the surgery, there would be a very good chance that the nerve could be damaged, leading to permanent impotence.

Furthermore, a lot of prostatectomy patients have urine leakage after the surgery. At the age of 47, I wasn’t willing to sacrifice my sexual function and be forced to wear a diaper for the rest of my life.

I also learned that many men survived radiation therapy pretty well initially, but the same negative side effects of the radical prostatectomy started appearing 18 months to three years after the radiation. The radiation also regularly caused rectal damage and urethral strictures.

Neither the surgery nor the radiation side effects were acceptable to me. I chose not to seek treatment at the time. I elected to have five to 10 years of a relatively normal life before dying of cancer instead of seeking treatment and experiencing 25 more years of life without sex and wearing a diaper.

I rapidly grew accustomed to the fact that I would have a five to 10 year life expectancy and I chose to maximize those years I had left. After getting used to the idea, my impending death actually turned into something positive. Many of the stresses of daily life simply evaporated.

– I had no concerns about money. With my police pension, teaching/writing income, and savings, I could live a quite extravagant life and still have plenty of money for a 5-10 year lifespan.

– No relationship stresses. I quickly learned that most women didn’t want to get involved in a long-term relationship with a dude who would be dead in the next five years. Consequently, I stopped pursuing long term romantic relationships. Until then I didn’t realize how much energy I was expending seeking a long term romantic partner.

– I have a family history of Alzheimer’s disease/dementia. There isn’t much of a chance of me getting that before age 55. Likewise, I have a hereditary retinal condition that will eventually cause my complete blindness. I’ll probably die from the cancer before that happens.

– Other health concerns? None. I could eat and drink as much as I wanted. The cancer will finish me long before I will die from heart disease or liver failure.

– In my final years as a cop, I became fearless. Getting killed in a gunfight at work was a far better way of going out than a painful death from cancer. I was able to take chances that most cops would never consider because I already knew I was dying. Nothing I could experience at work could be worse than that.

I actually came to embrace my upcoming death. Unlike most people, it provided me with a bit of solace and insulation from the career/money/relationship/health stresses that everyone else on the planet has. I lived life like a Bukowski poem:

“Most people are not ready for death, theirs or anybody else’s.

It shocks them, terrifies them.

It’s like a great surprise.

Hell, it should never be.

I carry death in my left pocket. Sometimes I take it out and talk to it: “Hello, baby, how you doing?

When you coming for me?

I’ll be ready.”

– Charles Bukowski

With all that said, I remained open to the idea that in the future a better treatment would be developed. I never wanted to die early, I was just OK if that was the natural outcome of my condition. Since my diagnosis almost three years ago, I’ve continued to monitor my PSA levels and live life to the fullest.

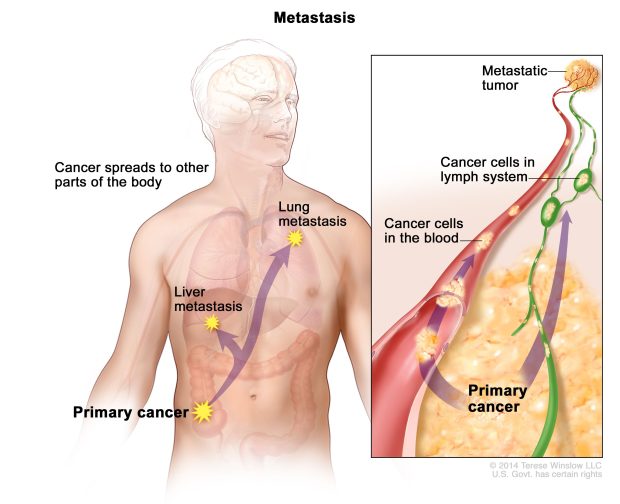

From all my research I knew that the earliest the cancer was likely to spread was when my PSA reached a level of between 15 and 20. It was most certain to spread somewhere between 20 and 100. Once the cancer metastasizes, my treatment options become more limited. After it spreads, the treatment is general androgen deprivation (chemical castration, the cancer needs testosterone to grow) and focal radiation treatment for the bone/lung mets. I wasn’t willing to do that. My only possible chance for treatment was to do something before the cancer spread.

I spent the intervening three years ignoring my cancer and living my best life. Last July, I got my biannual PSA test. My PSA was 12.6, up from 8.4 six months earlier. That was a big jump and it was getting really close to that “15” level where the cancer starts spreading. If I wanted to do something about the cancer, I needed to do it in the 6-12 month time period before the cancer metastasized.

Earlier in my cancer journey, I had corresponded with a reader (thanks Donn!) who suggested an alternate treatment called TULSA. He had prostate cancer and had his cancer ablated via the TULSA procedure with neither impotence nor incontinence. It was a newer procedure and it wasn’t covered by insurance. There was little long term data on it, but it appeared promising.

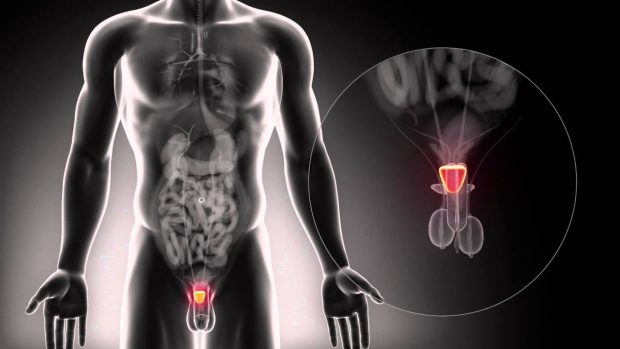

I booked an appointment with my reader’s doc to have an MRI and discuss the procedure last month. The TULSA procedure uses trans-urethral high frequency ultrasound waves to destroy the cancerous tumors and lesions in the prostate. What makes it unique is that the procedure is done while the patient is in an MRI machine that monitors tissue temperatures. The doctor doing the procedure can see the nerves that control sexual function and ensure that they aren’t damaged by the heat from the ultrasound as the cancer is destroyed. Additionally, the doctor can see and avoid damaging any of the urinary sphincters that might cause incontinence.

I flew to Atlanta and underwent a high sensitivity MRI. The MRI showed my cancer had grown significantly in three years. The highest grade tumor was nearing the wall of the prostate capsule. Once it breaks through the wall of the prostate, it would start to quickly spread to my bones and lungs. The radiologist estimated that I had less than six months before the cancer broke free and metastasized. I was out of time. I could choose to either treat the cancer or expect a very painful death within the next 2-3 years.

The TULSA procedure is only about six years old, so there isn’t any long term success data. So far, 93% of the patients who have undergone the procedure worldwide have remained cancer free.

The doctor I visited has done 215 of the procedures. NONE of his patients have incontinence. Only five of the 215 have erectile difficulties and all five of those patients are able to have sex with either Viagra or a Tri-mix injection. The odds are pretty good that I will emerge from this surgery with a far smaller likelihood of the sexual/urinary side effects I wanted to avoid with the radical prostatectomy.

Even if the surgery only prolongs my life another five years, with the relatively small chance of side effects, I think it’s worth the risk. I scheduled the surgery for early January.

I had become so accustomed to the idea of dying early, that I actually had a hard time making the decision to undergo this procedure. Now that I have a good chance of living beyond a couple more years, I have to start worrying about money, relationships, and other aspects of my health again. That was honestly quite a difficult mental shift to make. I hope I’m making the right decision.

My late friend Marcus Wynne knew about my cancer journey and urged me to write about it. Until now, I have avoided that. Marcus predicted that the lives I could change from telling my cancer story would far exceed the lives I might save from all of my tactical and travel writing. I told Marcus he was insane. Now I’m not so sure. I hope hearing about my situation can help some folks who suffer from similar maladies.

I haven’t been the most responsive to course hosts in the last few months. I have a lot of emails and phone calls I’ve ignored for awhile because I’ve been dealing with the cancer stuff. I hope to rectify all of that soon. I didn’t write this narrative looking for sympathy or money. I’ve already paid for the surgery and I’m good to go. All I ask for is a bit of grace in consideration that I’ve had an awful lot on my plate and I haven’t been able to give my full attention to my business, my writing, and my personal relationships lately.

I’ll take all the positive thoughts and/or prayers you are willing to offer. I’ll let you all know how the surgery turns out. Thank you for your support.