Written by: Greg Ellifritz

Dan Ariely’s book The Upside of Irrationality is a book about making rational and irrational decisions. Books like these are a goldmine of information for firearms and combatives trainers. We regularly see people making irrational decisions in the context of self defense. It’s nice to figure out why they are doing so with the hopes that we can correct the behavior in our students.

When reading the book, two specific passages stuck out for me. Both were relevant to defensive training, more specifically to scenario oriented training classes. Force-on-force scenario training is very difficult to do well. Here are a couple of tips from me (using research from the book) to help you get it right.

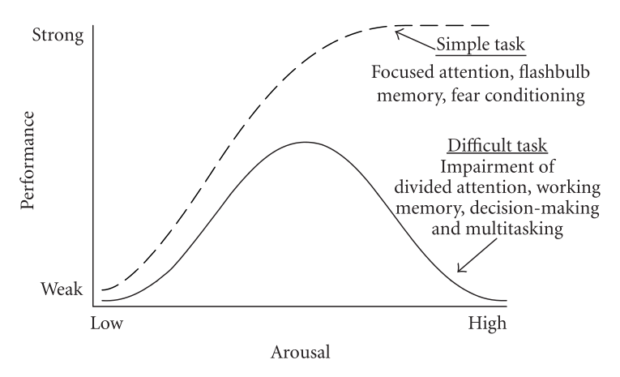

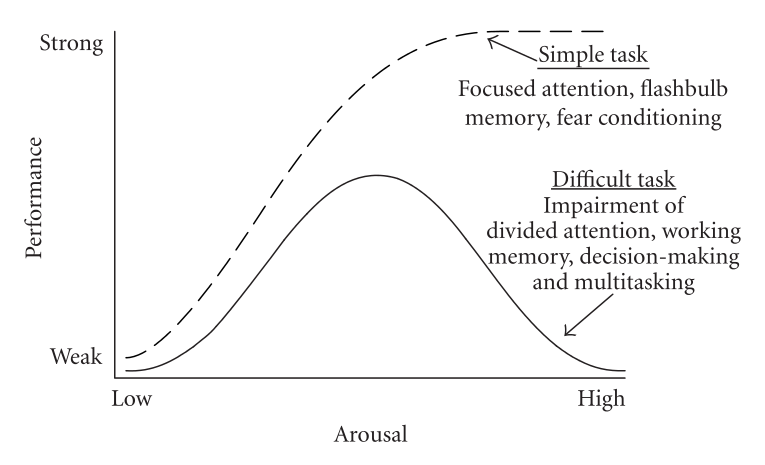

1. We trainers have to understand the “inverted U hypothesis” and the “Yerkes Dodson Law.“ Student motivation can be graphed with an “inverted U relationship.” Some stimulus makes the students perform better. Too much of that same stimulus creates poor performance. Check out the quote from the book below:

“SOMETIMES OUR INTUITIONS about the links between motivation and performance (and, more generally, our behavior) are accurate; at other times, reality and intuition just don’t jibe. In Yerkes and Dodson’s case, some of the results aligned with what most of us might expect, while others did not. When the shocks were very weak, the rats were not very motivated, and, as a consequence, they learned slowly. When the shocks were of medium intensity, the rats were more motivated to quickly figure out the rules of the cage, and they learned faster.

Up to this point, the results fit with our intuitions about the relationship between motivation and performance. But here was the catch: when the shock intensity was very high, the rats performed worse! Admittedly, it is difficult to get inside a rat’s mind, but it seemed that when the intensity of the shocks was at its highest, the rats could not focus on anything other than their fear of the shock. Paralyzed by terror, they had trouble remembering which parts of the cage were safe and which were not and, so, were unable to figure out how their environment was structured.

The solid dark line represents Yerkes and Dodson’s results. At lower levels of motivation, adding incentives helps to increase performance. But as the level of the base motivation increases, adding incentives can backfire and reduce performance, creating what psychologists often call an “inverse-U relationship.”

Inverted U Hypothesis diagram from Wikipedia

Relate this to scenario training. When we conduct scenarios with too much stimuli, the student will perform poorly. That shouldn’t be your goal as a trainer. We can all create unwinnable scenarios, but those don’t make our student perform any better. In your classes, start your lesson out by designing scenarios that are extremely easy. Let the student succeed. As his skills and confidence increase, gradually add more and more stimuli. Creating a scenario where a student has to fight 25 ninjas rappelling from the ceiling isn’t a good way to make our students better. Gradually build up the stress. Don’t give the students the test before you’ve taught them the lesson.

2. Some pain in training is good. I really like using Simmunition rounds in training. Some folks hate that (because it hurts when you are hit), but experiencing pain in training makes people more capable of enduring higher levels of pain in real life after the training is over. The book describes a test where the participants were forced to put their hands into hot water for as long as possible and looked at how previously injured people who had sustained minor injuries dealt with the pain of the hot water versus those people who had previously experienced the pain of a more serious injury:

“The participants who had been mildly injured reported that the hot water became painful (pain threshold) after about 4.5 seconds, while those who had been severely injured started feeling pain after 10 seconds. More interestingly, those in the mildly injured group removed their hands from the hot water (pain tolerance) after about 27 seconds, while the severely injured individuals kept their hands in the hot water for about 58 seconds.”

“The happy ending? Hanan and I discovered that we were not as odd as we thought, at least not in respect to our pain response. Moreover, we found that there seems to be generalized adaptation involved in the process of acclimating to pain. Even though the people in our study had endured their injuries many years before, their overall approach to pain and ability to tolerate it seemed to have changed, and this change lasted for a long time.”

Hard and/or painful training is worthwhile. Students can use their previous training experiences to overcome the pain of future experiences. If they have never fought through any pain or discomfort in training, they won’t do as well when they experience pain in real life.

If you are a trainer, you owe it to yourself to keep up with the latest research. Your students are relying on your knowledge. Don’t let them down. The Upside of Irrationality is available on Amazon or at your local book seller.

Some of the above links (from Amazon.com) are affiliate links. As an Amazon associate I earn a small percentage of the sale price from qualifying purchases.

If you would like to further support my work, head over to my Patreon page.