Written by: Greg Ellifritz

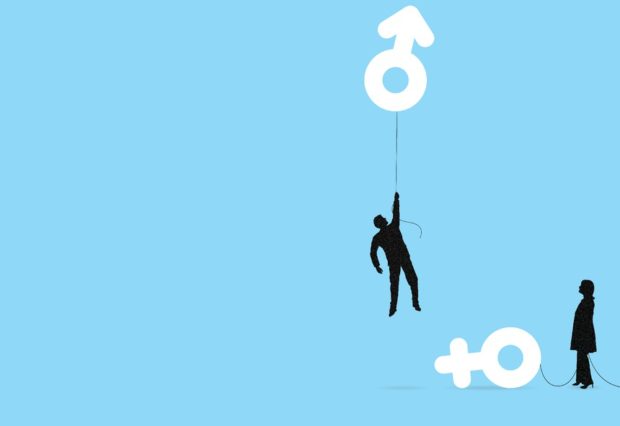

I was recently reading a very interesting article titled “The Confidence Gap.” The article described how in general, women had far less self-confidence than men. A couple of examples cited are:

– In a British managerial study “Half the female respondents reported self-doubt about their job performance and careers, compared with fewer than a third of male respondents.“

– In a questionnaire self-assessing scientific knowledge “The women rated themselves more negatively than the men did on scientific ability: on a scale of 1 to 10, the women gave themselves a 6.5 on average, and the men gave themselves a 7.6. When it came to assessing how well they answered the questions, the women thought they got 5.8 out of 10 questions right; men, 7.1. And how did they actually perform? Their average was almost the same—women got 7.5 out of 10 right and men 7.9.”

The overall conclusion of the article?

“In studies, men overestimate their abilities and performance, and women underestimate both. Their performances do not differ in quality.”

This isn’t the first time I’ve heard of such research. Early in my teaching career, I remember reading something very similar in Carol Wiley’s 1995 book Martial Arts Teachers on Teaching. In an essay in the book titled “One More Way“, Barbara Summerhawk made the statement:

” At the risk of generalization, men are too often complacent in their physical strength and women too often lacking in confidence.”

Strength coach Tony Gentilcore commented on essentially the same phenomenon in his article Some Thoughts on Training Women. In that article, he makes the following point that may partially help to explain the “confidence gap.”

Men tend to be more Temporal Comparative, where they compete or compare against themselves.

What did I deadlift last week?

What did I squat last week?

How much do I weigh now compared to last month?

Guys tend be more interested in what they, themselves, are doing.

Conversely, women tend to be more Societal Comparative, and compare themselves to other women.

She’s doing “x” amount of weight on the bench press, how come I’m not doing that much?

She has an amazing back. Why doesn’t mine look that way?

I can’t believe she’s wearing that to the gym. What a ho!

While Tony’s examples are obviously fitness-related, I see the same things happen in shooting classes. My female students often have less shooting experience than their male counterparts. When they compare themselves to the more experienced shooter, they feel bad. That leads to a drop in confidence.

Why is this issue of the “confidence gap” important? A quote from the original article explains it all:

“When people are confident, when they think they are good at something, regardless of how good they actually are, they display a lot of confident nonverbal and verbal behavior,” Anderson said. He mentioned expansive body language, a lower vocal tone, and a tendency to speak early and often in a calm, relaxed manner. “They do a lot of things that make them look very confident in the eyes of others,” he added. “Whether they are good or not is kind of irrelevant.”

Kind of irrelevant. Infuriatingly, a lack of competence doesn’t necessarily have negative consequences. Among Anderson’s students, those who displayed more confidence than competence were admired by the rest of the group and awarded a high social status. “The most confident people were just considered the most beloved in the group,” he said. “Their overconfidence did not come across as narcissistic.”

In a self defense context, a lack of self confidence causes women to display body language that may lead them to be victimized at a higher rate. That’s a problem.

What do we do about the confidence gap?

For men, the answer is easy. They just need a more realistic assessment of their true skill levels so that they don’t commit errors of overconfidence. Enrollment in training classes will expose the male’s weaknesses. So will competition. Both are highly advisable for any man looking to improve his combative abilities.

What about the women?

The article makes a great suggestion:

“The advice implicit in such findings is hardly unfamiliar: to become more confident, women need to stop thinking so much and just act. And yet, there is something very powerful about this prescription, aligning as it does with everything research tells us about the sources of female reticence.”

In essence, the article suggests an attitude of “just do it.” I think that’s great advice. In the context of firearms or self-defense training, women need to recognize that their fellow students aren’t likely paying much attention to them. They are too busy doing their own things. Go to class. Just do it.

Looking at Tony’s statement above, I might also suggest that women adopt the male attribute of “Temporal Comparative” thought. Tracking tangible and measurable performance improvements over time might increase the confidence of a woman better than merely comparing herself to her peers.

So, in summary, men need to recognize they aren’t quite as studly as they think they are. Women need to recognize that they are far more competent in the context of fighting than what they have been led to believe. A change in attitude for both sexes will lead to better performance.

Men tend to be more Temporal Comparative, where they compete or compare against themselves.

What did I deadlift last week?

What did I squat last week?

How much do I weigh now compared to last month?

Guys tend be more interested in what they, themselves, are doing.

Conversely, women tend to be more Societal Comparative, and compare themselves to other women.

She’s doing “x” amount of weight on the bench press, how come I’m not doing that much?

She has an amazing back. Why doesn’t mine look that way?

I can’t believe she’s wearing that to the gym. What a ho!

– See more at: http://www.tonygentilcore.com/blog/some-thoughts-on-training-women-post-i-dont-know-i-lost-count/#sthash.OR0wsxhr.dpuf